Gurus, Landslides, Bhutan, Oh My!

“Let your mind rest like the center of space.”

— Guru Shri Singha, “Crystal Cave”

—————————

It was January of the new millennium. After a peripatetic year and a half in the West, it felt so good to be “back home,” upstairs at Chatral Rinpoche’s monastery in Pharping. I had a practical gift for Rinpoche: a thick red fleece cap from Eastern Mountain Sports in New York, and a similar red fleece cap, lightweight and kidsize, for the “Little Prince” of dharma, nine-year-old Dudjom Yangsi Sangye Pema Shepa. After offering the hats to the precious duo, I righted myself back down on the carpet at Chatral Rinpoche’s feet. Without missing a beat, Rinpoche handed me a well-worn red fleece hat of his own.

Lama Khyenno! My mind fell away. My heart was thumping, loudly. I looked to Chatral Rinpoche to see if it would be okay for me to place His hat on my head, in His presence. Yah, yah―fine. I looked in Dudjom Yangsi’s direction. Yangsi understood. Chatral Rinpoche donned his new fleece hat.*

Oy!—it needed to be cut for a proper fit! But Rinpoche sat there sporting the red thingy with an air akin to Dr. Seuss’ unflappable Cat in the Hat. Dudjom Yangsi donned his kid-size hat. And then it was my turn. On adorning myself with Chatral Rinpoche’s hat, I spontaneously broke into song, reciting the Tibetan verse of The Bodhicitta Prayer to a tune I learned from a hauntingly beautiful rendition of it by Zenkar Rinpoche.

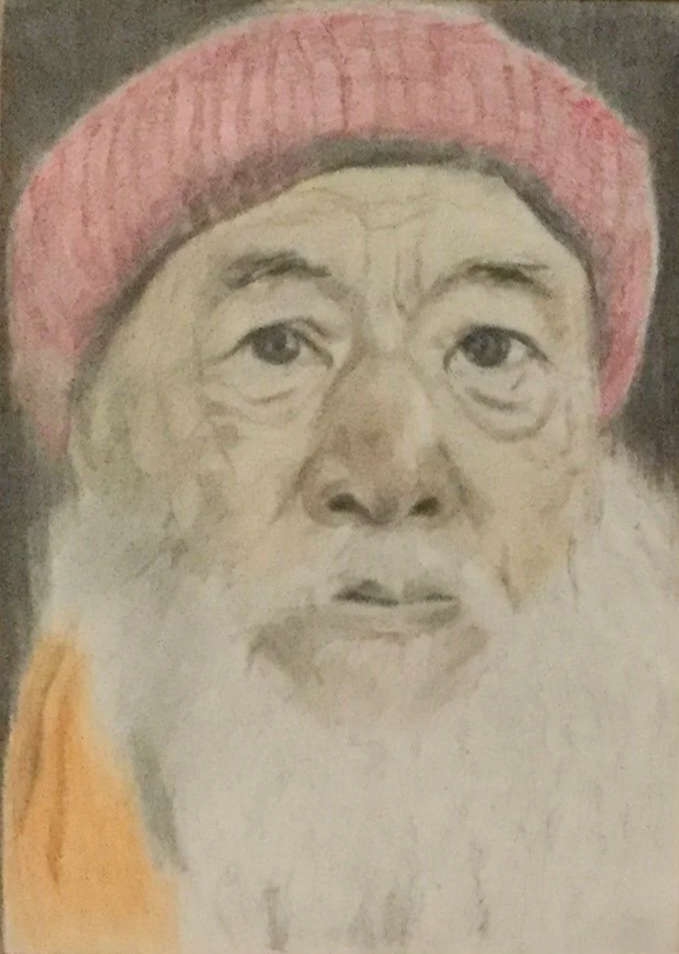

HH Chatral Rinpoche (Portrait by N. L. Drolma)

Chatral Rinpoche’s hat became part of my guru yoga practice. I wore it daily and resolved to be mindful of where I put it when taking it off. Every so often, I’d absentmindedly place the hat aside, only to spend hours later retracing my steps to find it. Each time this happened, I’d chide myself, Hey, don’t be stupid; put the hat on your shrine.

Other faithful devotees might well have placed the hat on their shrine as this hat was imbued with the blessings of a master regarded by the wise and learned to be an Awakened One. I, however, continued to wear the hat until the day came when I lost it for good. My lack of mindfulness surely catalyzed for the stranger who found the hat a singular karmic link with HH Chatral Sangye Dorje Rinpoche.

* The Nyingmapas are known as the “Red Hats.” To signal their erudition, Nyingma scholars of great accomplishment are formally crowned with a highly stylized red cap adorned with gold piping and long ear flaps.

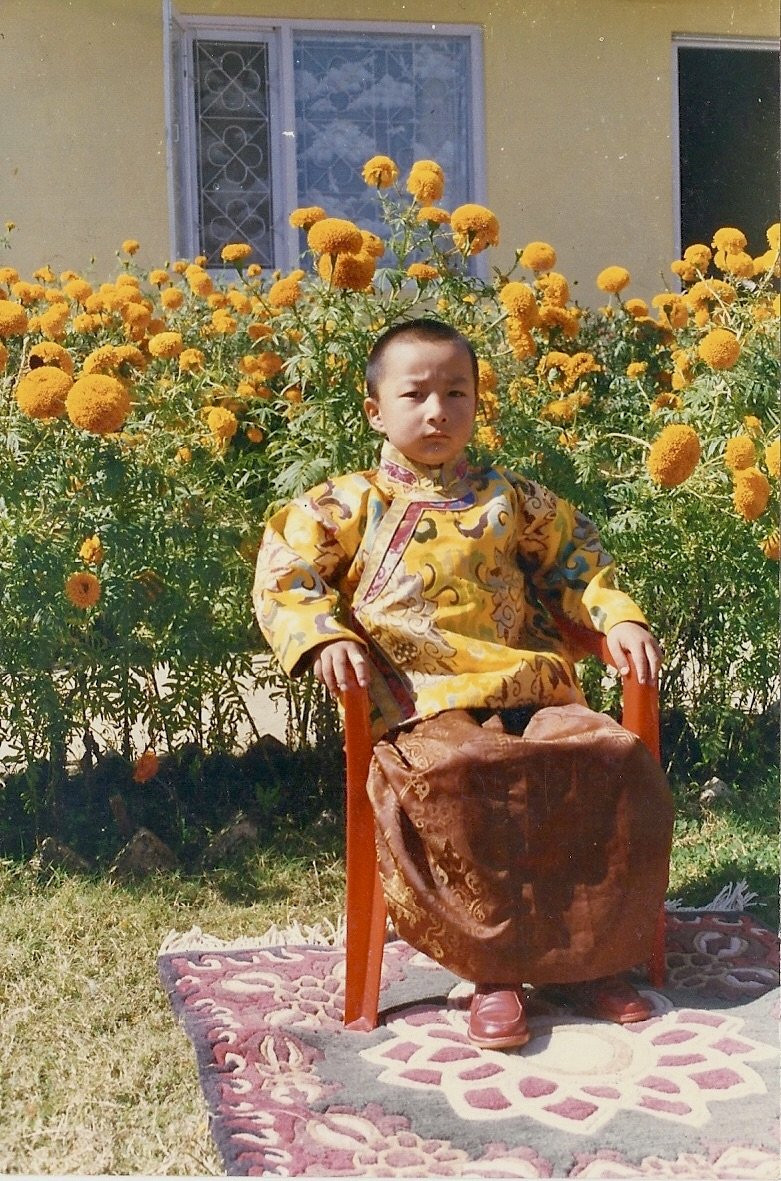

Dudjom Yangsi, age 7, crowned by marigolds. Pharping, Nepal 1997. (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

In Dudjom Yangsi’s presence, it was clear that wisdom has no age. This photo (which I took at Yangsi’s request) was the first of many I would take of the precious tulku. The day was extra special because I was meeting Yangsi for the first time; the occasion a stunning serendipity that filled me with happiness beyond conception. Yangsi was Guru Rinpoche to the manner born, his comportment regal, unstudied and disarming. Dudjom Yangsi’s penetrating gaze, soft smile, calm and overall serious disposition belied his age (as did the mellifluous, even-tempered cadence of his speech later in his teen years). At the tender age of eight, Dudjom Yangsi told me: “Guru Rinpoche is always with you. It’s just that we’re not seeing him. When we look, we see only the trees and this earth.”

Kathok Situ Rinpoche served as translator for the 20-minute “Q&A” that I recorded on audio cassette with the Dharma wunderkind. (Kathok Situ’s picture is the third image on the reel in the Portrait Gallery.)

“I’m the most fearless kid!” Yangsi declared.

Yup. No doubt about that.

Dudjom Yangsi Sangye Pema Shepa with his devoted attendant Norbu, two local boys, and young French monk in Pharping, Nepal 1997 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

N. L. Drolma’s first guru was Dr Seuss, author and illustrator of “The Cat in the Hat;”this vintage drawing unarguably precursor to Mahaguru Portraits.)

Dorje Drolo, one of Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche. 18th c. pigment on cloth (25” x 18”), Rubin Museum of Art, Gift of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation

In 8th century Bhutan, Guru Rinpoche manifested as the potbellied, crazy wisdom master Dorje Drolo to subjugate negative forces at Tiger’s Nest. His mount was a pregnant tigress! I felt drawn to the holy site of Tiger’s Nest and wanted to visit the Kingdom of Bhutan ever since the awesome week back in '93 when it was my good fortune to host Nyoshul Khenpo and his Bhutanese wife at my home in New York City.

Seven years later, I found myself traveling by jeep— not tigress —along the 169 kilometer route from Chorten Gompa in Sikkim to Bhutan: Land of the Thunder Dragon.

All was going well until we reached a dead end at an Indian village near the Bhutanese border. A labor strike had banned all cars and buses and shut down all shops. We were stranded in a no-name town, with no westerners in sight, and no one who spoke English except for my driver.

I recalled with immense relief that Seymo Saraswati, months prior to this journey, gave me a number to call in Bhutan should I need help. To circumvent the transit ban, a Phuentsoling native sped to my rescue via motorbike. It was thrilling to enter Bhutan in such a spirited, fun way—balanced on the back seat of the gentleman’s bike— my first motorcycle ride ever.

My Bhutanese hero left me at the border momentarily to scoot 7 kilometers back for my luggage which the Gangtok jeep driver had nobly guarded.

It was monsoon season. There were reports of severe landslides, and it was recommended that everyone refrain from unnecessary travel. I was advised not to go up into the mountains, but to stay at a hotel in Phuentsoling. I didn’t like this news at all. The next morning, I did a “mo” (divination) confirming that I should book a hotel. I visited a few hotels to check out the accommodations. One was dreary beyond repair, resembling storage space for used furniture and crates gone topsy-turvy. Another was evocative of a giant flimsy hatbox. The third, a so-called luxury hotel was clean enough, but its deserted energy field off-putting. Most of the rooms were unoccupied. Not keen to sit in an empty hotel, I was fixated on Thimpu—or bust! And so I did another mo: Pay the twenty-five dollars and stay in the luxury hotel. I walked slowly, grudgingly to the front desk to book a room I didn’t want. The concierge suggested I take a look at another suite and proffered the key. At that moment, a stranger ran up to me and said he found a good car and a driver willing to go up the mountain. I placed the room-key down on the front desk and walked outside to meet the driver and appraise the car. My gut warned me: Don’t go up the mountain.

The hotel’s check-in desk was several yards away, the car door at my fingertips. I pressed the door latch and waved a hearty good-bye to the hotel clerk.

Tiger’s Nest, Thimpu, Bhutan (Postcard photo: R. Dompnier; rainbow starlight by N. L. Drolma)

The driver put my bags in his trunk, and we were off to Thimpu! I wanted so much—too much—to reach Thimpu by nightfall. A few hours later, our car was stopped by the highway police patrol. New landslides were reported and we were advised to turn back. “Oh no, must we turn back?” I asked. I had zero interest in spending a single day of my two-week visa languishing in a hotel.

The taxi driver was an accommodating fellow. “Okay, don’t worry. We can stay where we are, sleep in the car, and continue up the mountain tomorrow, how is that?” I felt safe with this driver, and I thanked him for the offer. My fellow passenger, a gentleman we picked up earlier along the way, was frightened and wanted to go back down the mountain. Our driver found him a car going down. It was now around 7 p.m. By 9 p.m., I was curled up in the back seat of the cab, with my backpack for a pillow. The cab driver graciously offered his spare blanket to supplement my sleeping bag. This was the first time I had occasion to sleep overnight in a car, and looking out the car window at the evening stars made me feel like a pre-teen on a sleepover with a friend. All 5-feet 8-inches of me, however, was no longer a spry child. It was hard to settle into a comfy position on the compact sedan’s narrow seat. But sleep overtook me soon enough, and when I woke up at 4 a.m. I was happy to be on the mountain highway and not back at the hotel in Phuentsoling.

My driver later apologized, informing me that he had to go down the mountain but would not do so before finding a truck or car that could take me up to Thimpu. This news was disconcerting, but determined as I was to not turn tail, I settled into the front seat of a huge truck whose driver was pleased to accommodate me; he and the taxi driver were friendly acquaintances. Later, the trucker, too, offered me his apologies. He was transporting fish and couldn’t be parked indefinitely on the highway. More and more cars and trucks began inching their way down the mountain in single file. I was definitely bucking the trend.

Finally, around 3 or 4 p.m., a few of the cars and trucks lined and parked up ahead restarted their motors and were moving forward along the mountainside. I was no longer sharing a trucker’s elevated, front-seat view of the landscape; my Disney carriage was the back seat of a dented, tin shell of a car and I was feeling every single bump in the road. At one point while I was resting lightly against the car door, the door flew open as my driver veered sharply around a bend in the terrain. “Jeez, loose hinges,’ I murmured to myself. ‘Just don’t lean against the door, and you won’t go tumbling off into space.” On the bright side, I was having an adventure in Bhutan, and it was more colorful than sitting in an antiseptic hotel room.

The Bhutanese landscape was enchanting. I half expected Rapunzel’s stone castle to materialize, along with Peter Pan, and Tinker Bell. The stark beauty made it easy enough to regard the distant cliffs and boulders above our narrow winding road as nothing more than trompe-l’oeil or blocks made out of papier-mâché. Fear of landslides had no foothold, such was my joy at the prospect of practicing in Nyoshul Khenpo’s home. It was late evening when the taxi pulled into Kalu Rinpoche’s monastery. I was greeted by Kalu Yangsi’s mother, Mayum Drolkar, who kindly arranged for a government permit which excused me from the $250 per diem required of visitors to Bhutan. I was to be Mayum-la’s houseguest for a few nights and then join her for the car ride to Khenpo’s home.

◊

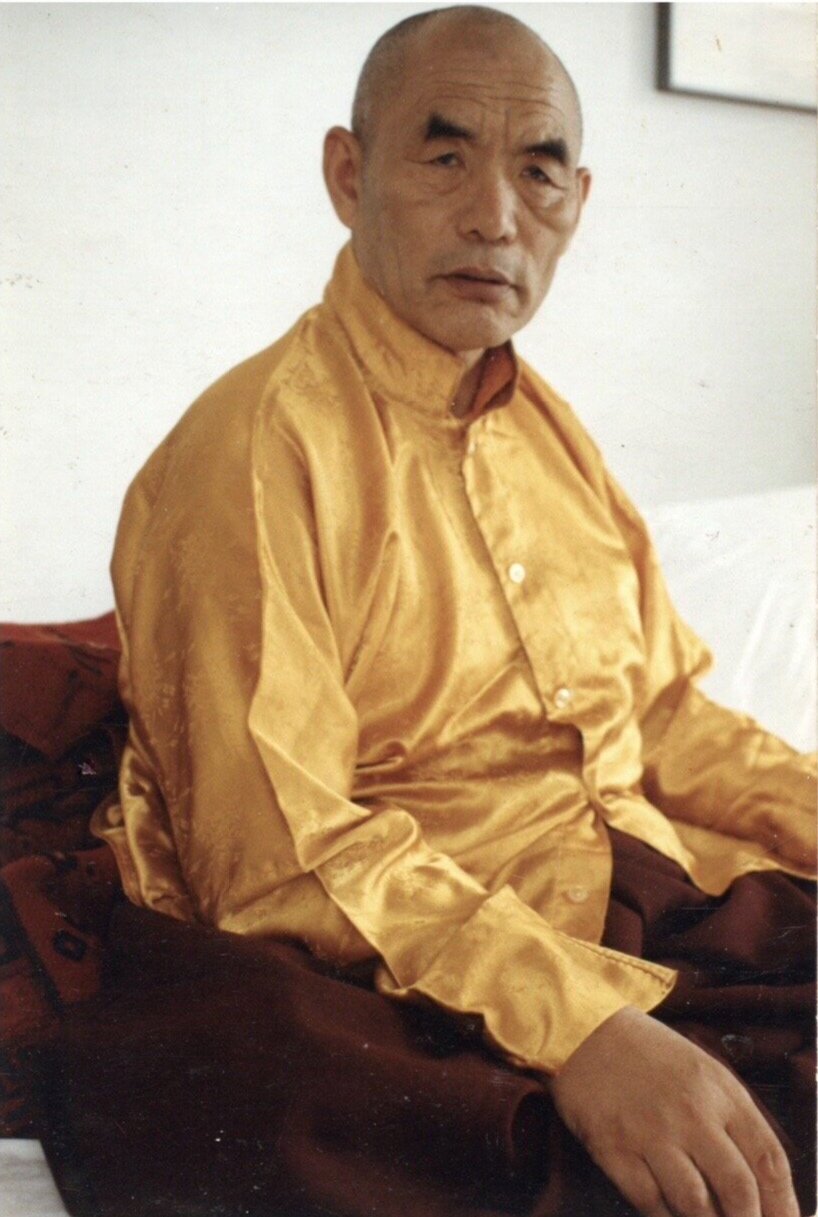

Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche, Khachod Dechen Ling, NYC 1992 (Photo by N. L. Drolma)

A low buzz of voices swept through the shrine room and suddenly the lamas were on their feet, pushing en masse towards the exit: All were eagerly lining up along the driveway of Khenpo’s home to honor the imminent arrival of HH Chatral Rinpoche, who was in town as a guest of the Grand Queen Mother of Bhutan. Chatral Rinpoche would be joining us for puja. A la la ho! It was Shakyamuni Buddha Day and the last day of Saga Dawa—a most auspicious day to commemorate the life and legacy of Nyoshul Khenpo and a powerful month for practice in the Tibetan calendar, signaling the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and parinirvana.

Within minutes of taking his seat, HH Chatral Rinpoche was swamped with offerings and requests from a stream of lamas. I presented a customary monetary offering and asked Ozer Tulku, who was assisting Rinpoche amid the pandemonium, if Rinpoche would please bless a special bell and dorje given to me by Khandro Tsering Chodron’s cook, a gentle monk and disciple of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche. The bell and dorje were specially crafted in Tibet and Khandro-la had tied them tightly together with a white khata.

HH Chatral Rinpoche wearing the Kathok Hat. (Photographer and date unknown)

Chatral Rinpoche untied the tantric objects and made an appreciative remark as he rang the bell to his ear. Its tone was beautiful, indeed. Rinpoche rang the bell again, and again, and then put it aside with the dorje. He didn’t formally bless the ritual implements, nor did he hand them back to me. Ozer Tulku’s attention was elsewhere and my confusion dissipated with the monks sounding the Tibetan horns and clanging the cymbals. Puja had resumed.

A rousing chant of Narak Kong Shak, the king of confessional prayers, was under way and I was delighted to have at hand the Tibetan phonetics along with an English translation. It was the rare occasion when I could join in with a chorus of monks reciting a lengthy text.

The following day at lunch with Seymo Saraswati, I learned that Ozer Tulku’s English is spotty, that he didn’t convey my request of Chatral Rinpoche to bless the bell and dorje. I was both amused and taken aback when Seymo-la told me I could come and pick up the ritual objects anytime; they were stashed in her room with all the other offerings. During puja, however, I concluded that I made a material offering by default! How could I make it a bonafide offering? By reflecting on the meaning of the bell and dorje and offering up (letting go of) my attachment to the sacred objects. And that’s what I did—joyfully, as if prodded to do so by Nyoshul Khenpo, whose life exemplified the wisdom of non-attachment.

Semola Saraswati Rinpoche on horseback in Bhutan (Photographer/ year unknown).

One afternoon of glorious sunshine, I found myself sitting alone with Seymo Saraswati atop a hillock that offered an unobstructed, panoramic view of Bhutan’s pristine greenery. It was a sweetly intimate time. We were away from the usual buzz of people around Chatral Rinpoche and this allowed me to see Seymo-la in her own light, which was refreshing.

Seymo-la’s masterful insight— and ability to orchestrate the demanding world of people who came day in, day out requesting to meet with Rinpoche— won her renown as a supremely wrathful wisdom dakini. Seymo Saraswati’s ways are mercurial. She can be all four seasons in an hour and leave you cross-eyed in an instant. She is also wondrously light and her voice, bewitching.

Seymo-la informed me that “Rinpoche told everybody how Injee Ani was the only injee (westerner) present at puja.” What struck me as more odd than the absence of westerners was the virtual absence of women in the shrine room. (Btw, the moniker “Injee Ani” defined me for years; I thought the generic label was cute as well as on point for the lone western nun in Chatral Rinpoche’s mandala.)

Toward the end of my stay, Damcho-la ushered me into Nyoshul Khenpo’s bedroom and kindly left me there to sit alone, in homage to the guru. Sitting at the foot of Khenpo’s bed was the crowning moment of my pilgrimage to Bhutan. The atmosphere was one of blissful warmth, and of felicity beyond measure.